Memories of J. Preedy & Sons by Stanley Preedy

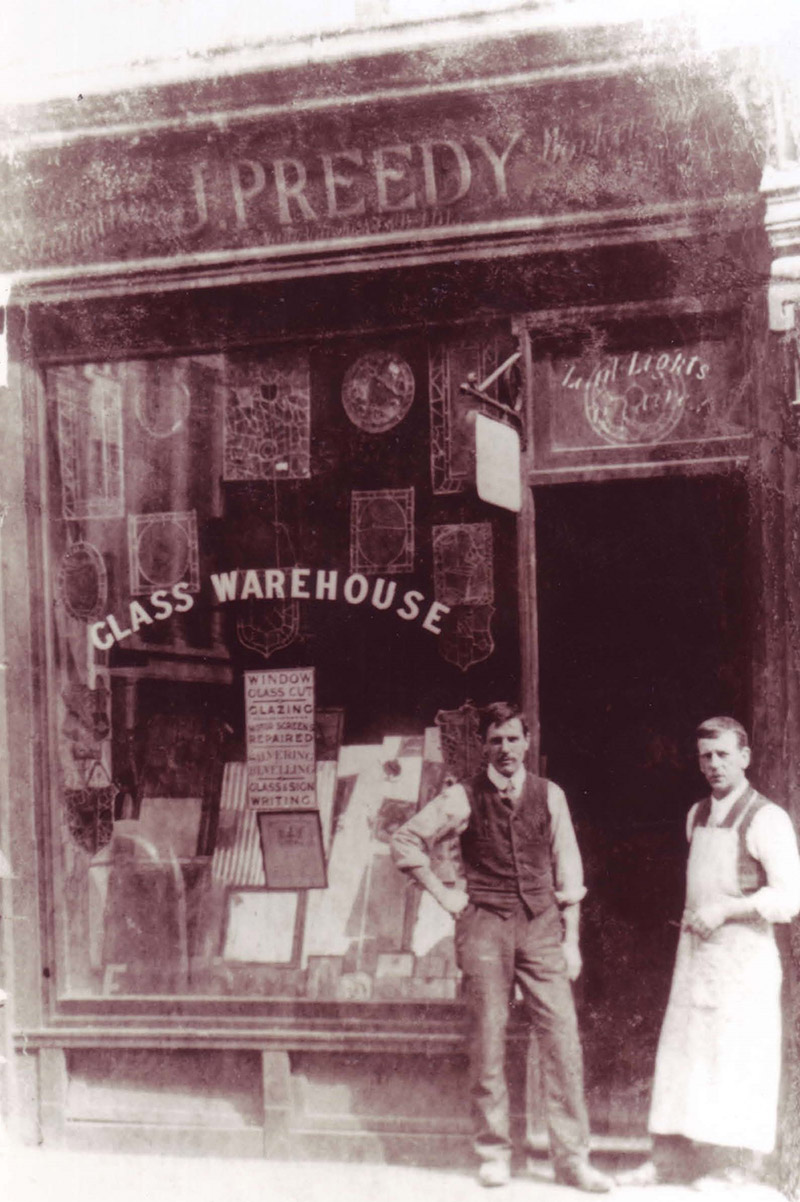

First shop

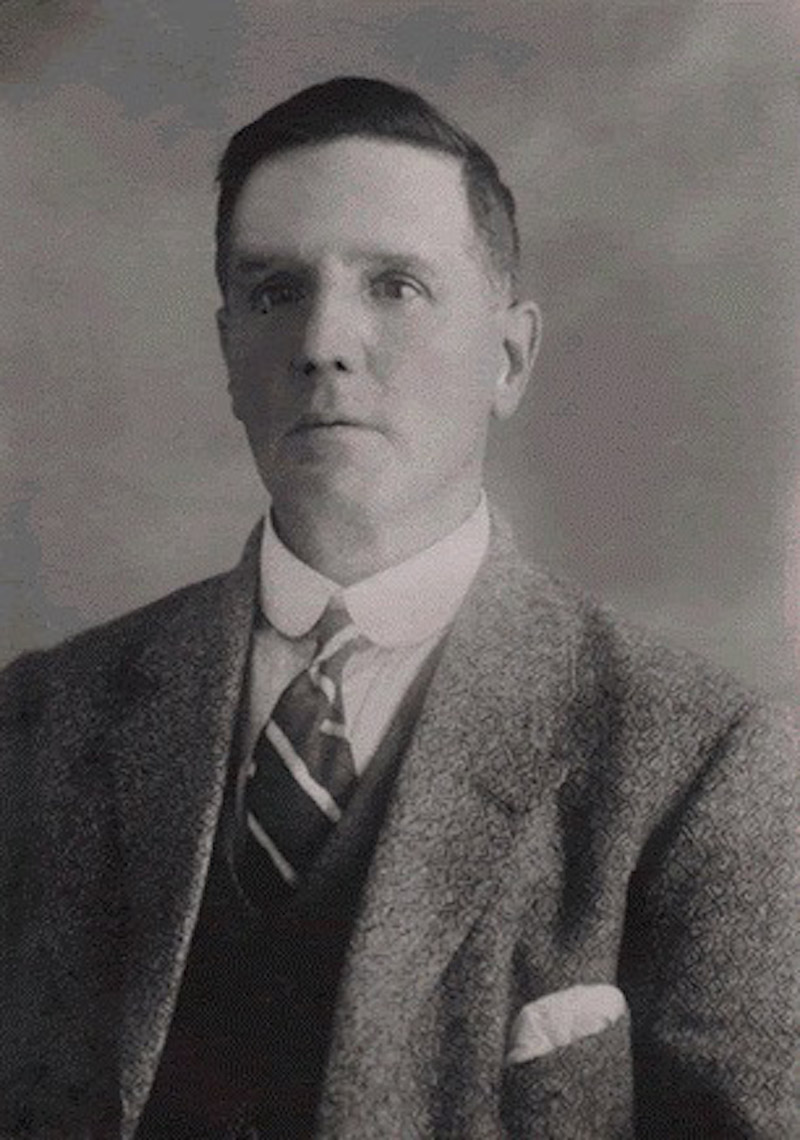

Joseph Preedy

Joseph Preedy started his glass business in 1913 in either Weymouth Street or Beaumont Street, London (W1G). He remained there for about six months before moving just around the corner to what is now Chiltern Street, where work continued on the production of lead lights, mirrors, and windows. These included stained glass windows which adorned numerous types of buildings, including public houses -not just the churches we have come to associate them with today.

Within a few short years Preedy Glass was coming to the aid of shopkeepers and homes after limited attacks from German Zeppelin’s during World War I.

Here, Joseph’s son, Stanley Preedy, recalls his earliest days in the company*.

“When I first started in the family firm, my first job was as delivery boy, pushing the firm’s barrow all over London having filled it full of glass the night before. At that time we were doing a lot of glazing work at the House of Commons, so each day I would push my barrow from Marylebone to Parliament Square. At other times I would walk as far as Shepherdess Walk in Islington and Upper Street in the City.

As time passed I enrolled at Regent Street Polytechnic, where two nights a week I took courses in shorthand and typing, commerce, book-keeping and accounts. This continued for about two years during which time I would go straight to the Polytechnic from work at six o’clock and not arrive back home until very late. These were exhausting times but essential if I was ever to bring value to the company.

As a glass merchant we dealt with most of the builders in Marylebone; I clearly remember there were about 50 local builders, many of which were quite small – apart from J. Simpson’s, who had their own saw mill and their joinery works on the premises. If you went down into a tunnel below their building you would see complete trees, such as oaks, pines and cherry.

Of the shops on Chiltern Street around the early 1920’s, I particularly remember Mr Haddock the undertaker who could be seen making coffins in his shop. He was a fabulous craftsman and would saw away at his trestle tables, labouring over his work. His funeral parlour was opposite the fire station, and when a funeral took place he would hire horses to pull the hearse, and he would lead the cortege in front with his black top hat tucked into the crook of his arm.

Among the shopkeepers in Chiltern Street was Mrs Creaton our neighbour; Mrs Creaton’s shop sold sweets and tobacco. On the opposite side were the Flowers, who were plumbers. They had a most beautiful little boy, an only child who reminded us of the child in the Pears Soap advertisements. Directly opposite us was the Artisans, Labourers & General Dwellings Company’s buildings, which were very run-down with communal bathrooms and toilets. The tenants used to send their rubbish down a chute to the ground floor where it rotted until the dustmen came and shovelled it into open carts and took it away.

Then there was a locksmith run by a Mr Brown; next door to him was Jones’s dairy shop, where I used to buy Mazawattee tea. Other shops included Frost’s removal firm, Gill, who did boot and shoe repairs, Gamble the fruiterer and Lords’, the tailors. In Dorset Street was Mr Long, the chemist and the Ottles’ bakery, from whom the nuns regularly collected the stale bread to help feed the deprived. We also had two doctors, Dr Blake and Dr Colwell, who made up their own medicines in their surgeries.

On the corner of Dorset Street and Chiltern Street stood the War Graves Commission office, a building that became the first home of Marks and Spencer who stayed there until they moved into their purpose-built offices in Baker Street, when Preedy Glass became a regular supplier.

But out of all the shopkeepers in Chiltern Street, the one I best remember was Arnold Wiggins, a picture restorer, framer and gilder. Mr Wiggins was a real Cockney and tended to put his aitches in the wrong place. He was a very strict employer and would frequently shout at his five or six young apprentices, but that was his manner and they remained loyal to him. Mr Wiggins did some marvellous work for the King, and when on one occasion the King visited his shop in Chiltern Street, he was surrounded by a swarm of police.

I also remember the Head Porter at St. Andrew’s Mansions in Dorset Street, who was always very smartly dressed in an Oxford Blue uniform with trimmed gold braid and a matching peak cap. He was very grumpy and would spend most of the day blowing a whistle to summon taxies for his tenants from a nearby rank.

The houses in Montagu and Bryanston Square were smart, very Upstairs Downstairs for those who can remember the popular British TV series; all had butlers, footmen, maids and cooks, and whenever I delivered glass table tops or mirrors to any of these addresses I would always be rewarded by the cook with a nice cup of cocoa.

During World War II, Preedy Glass was kept very busy replacing glass cracked or broken by enemy bombs for the Marylebone and Wandsworth Borough Councils. We also repaired and replaced stained glass windows to the Grocers’ Hall in the City, and polished plate glass windows at the Savoy Hotel in the Strand. In fact, we were so busy we had 30 glaziers working for us, including several who were women.”

After the war, we moved from our offices in Chiltern Street to Ashland Place, Paddington Street W1, and then opened a glass processing factory, Lamb Works in Islington, before moving into our existing premises in Park Royal on the edge of one of Europe’s largest industrial estates.

Although Stanley Preedy is no longer a part of our company, the fourth generation of our family glass and glazing business is still very proud to serve our environment and continues to enrich our history.

*Joseph Preedy had two sons, Stanley and Alfred